RICH MARS

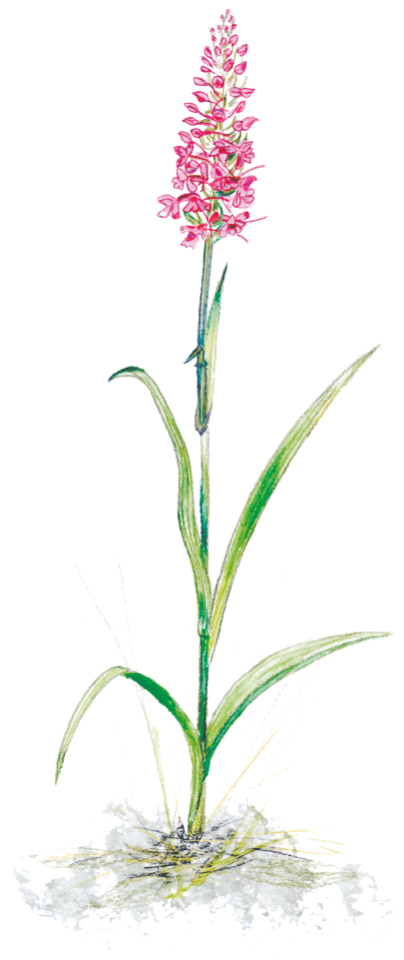

Marshes are a type of bog where plants are in contact with groundwater. Bogs can be categorised as poor bogs, intermediate bogs and rich bogs. Poor bogs occur mainly in areas with chemically acidic soils, e.g. in granite-dominated areas. In areas where rich bogs occur, the soil is more alkaline. The water in rich bogs is also rich in minerals. In these bogs, various species of orchids occur, such as meadow orchids, blood orchids, and maidenhair orchids. Grass wool, tufted sedge, snipe and hay flower are also common in the marshes. The bottom layer in the rich bogs is dominated by brown mosses. Intermediate bogs are intermediate forms between rich bogs and poor bogs. Extreme rich bogs are also called calcareous bogs and are a type of rich bog found only in calcareous regions. The water in limestone bogs has a high content of minerals, especially lime. Lime deposits are often found in the wetter parts of the marsh. Lime bogs are very rich in species and harbour a number of species indicative of lime. Examples of such species are axagus, head sedge, smooth sedge, hair sedge, glossy willow, flyflower and guckusko. Brown mosses dominate in the ground layer. Due to their species richness and the presence of rare species, the calcareous fens generally have very high botanical values.

OLD-GROWTH FOREST

On open land that is growing back, deciduous trees such as aspen and birch come first. In old-growth forests, such regeneration can occur after fires or storms. In the shade of the deciduous trees, the shade-tolerant spruce then grows up. At first it is slow. Eventually, after about 100 years, the most short-lived deciduous trees die. The previously shaded spruces now grow faster and form a spruce forest. As the spruce gets older, it becomes more susceptible to fungal and insect attack. Eventually, they die, often after being felled by storms. The gaps left by fallen or dead spruce trees provide space for new spruce and deciduous seedlings. The new trees in the gaps compete for space and nutrients. In the untouched spruce forest, trees of all ages are mixed with stumps and fallen trunks. This kind of spruce forest development can almost only occur in fire-protected areas. If the area is ravaged by fire, almost all the spruce dies because the bark is too thin to protect against the fire. This leaves the ground open again for deciduous trees.

Knottlarver

THE WATER STREAMS

Along the running water, in the shady ravine, at the stream's acidic trough and marshland, there is a very species-rich and varied environment separate from the surrounding forest. The stream is often shaded by dense bushes and a closed canopy. The sheltered and often moist environment has usually survived both forest fires and clear-cutting throughout history. There is often a large supply of dead trees and lying trunks. The high and even humidity and unspoilt nature mean that rare mosses, lichens and fungi can be found in stream ravines. The stream and its surrounding vegetation provide a refuge for many threatened species and allow animals and plants to spread between different forest stands. The water of the stream has its own animal and plant community. The environment is very sensitive to solar radiation, desiccation, nutrient leakage, damming and siltation.

Moths at different stages of development

FLOATING

The emergence of timber processing in the 18th and 19th centuries added economic value to the forests of Norrland, which would not have been possible without the cheap transport routes provided by water. The first rafts were made without permanent structures. Temporary structures were built with the help of the rafts to guide the timber through difficult passages. The timber was laid out on land and in the form of guide rods. At the end of the year, these devices were demolished and the timber used was allowed to follow the raft. Gradually, as logging became more extensive, it became necessary to clear the channels of stones and other obstructions and to install fixed devices to control the path of the timber and equalise the flow of water. Over time, special rafting companies were formed to provide rafting services for those using the river for a fee. In 880, rafting was given its own charter and legislation. The rafting companies were reorganised into rafting associations. The remains found today are often in smaller watercourses, where log driving ceased early and no clean-up has taken place. The stone part of the structure is often all that remains, but you can also find more or less decayed wooden structures of dams and log flumes.

FÄBODVALL

Cattle were brought to the pastures (Fäbodvall) in the summer to save the grazing land around the village. The cattle were grazed in the forests around the pastures, and the milk was used to make cheese, mash and butter. Seasonal herding is very old. Pastures are mentioned in the medieval landscape laws, and archaeological excavations of pastures date back to the Iron Age. Most pastoral farms existed in the 19th century. People usually moved to the pasture, or "buan" as it was also called, at the beginning of summer and stayed there until the end of September. It was often women who did the heavy and responsible work of herding. Younger boys and girls were also sometimes employed as herdsmen. The working day started early, sometimes as early as five in the morning. The cattle had to be milked, the cattle shed had to be mucked out and then the animals went out to graze in the forest. The milk had to be processed and used to make cheese, mash and butter. All kinds of objects had to be made, such as birch whisks, ladles and porridge crackers. The days were long and full of labour.

HUT

Sprucing up was a gruelling job with long and frequent waking hours. The kite could never be left unattended without constant supervision to prevent it from burning up. If there were two of you, you could sleep in shifts, but if you were alone, you could only close one eye at a time. Forest huts were most often used for overnight stays or for seasonal work. They were used by lumberjacks, log drivers, rafters and charcoal burners. Some huts were also built for hunting and fishing. The huts were often of a simpler type with a stamped earth floor. The interior consisted of a built-up hearth and one or two beds.

COAL MILE

Coal mining was common from the late 17th century until the late 1940s. During the Second World War, charcoal burning was greatly boosted. The last collieries in Sweden were built in the 1950s. Charcoal was used in iron production. Today, charcoal has been completely replaced by coal. Charcoal was produced by heating wood with limited access to air. At 270º C, the wood cools. Tar and gas disappear, leaving virtually pure coal. In the picture you can see a cross-section of a resmila. In the centre of the coal bed is a sturdy pole, the so-called king. Next to the king, an open drum has been saved to be used for lighting the millet. The wood is covered with rice and, at the far end, earth or charcoal sticks, all to reduce the air supply. The traces of old charcoal kilns are often characterised by circular surfaces overgrown with spruce and alder, and sometimes the remains of charcoal can be found deep in the ground.

LEAVES BURN

A deciduous burn is a forest stand that has developed naturally after a fire. The proportion of deciduous trees is significantly higher than in the surrounding coniferous forest. The tree species mix in a deciduous burn is dominated by aspen, silver birch, wych birch and willow. The deciduous tree layer is usually of the same age, but there may be occasional pine overhangs. The field layer is characterised by healthy vegetation types. It is not unusual for the deciduous fells to be roughly blocky and to be found on a more or less steep west-facing slope. Some deciduous fires may have conspicuously weak leaf stems and still contain rare species. When the burn is young, red-listed insects often appear, and the dead wood attracts the interest of woodpeckers. Where it has been carefully managed, older deciduous trees with red-listed species may be present. Over time, the deciduous burns change to deciduous coniferous forest.

STONE AGE SETTLEMENTS

Stone Age settlements provide evidence of a mobile hunting and trapping population. There are around two thousand known settlements in the county, the oldest of which are dated to the 6th century BC. Stone Age settlements are usually found along lakeshores and watercourses, but also occur in woodland and in the bare mountains. Stone Age settlements have usually left few visible traces. They are usually recognised by settlement material found superficially under the moss or washed up on the shore. The settlement material consists of waste from the manufacture of stone tools, known as rejects, and accumulations of burnt stone (sherd stone). Burnt stone is stone that has been heated and then cracked. Coking pits are usually round pits or depressions in the ground with a mound around the edge. The pit contains soot, coal and burnt stones. Hearths have been built from prehistoric times to the present and therefore occur in many variants. Hearths can be completely filled with stones or only consist of a stone circle. The prehistoric hearths are often located by watercourses. They consist of burnt stones and are often covered with vegetation. Settlement mounds Sometimes settlement mounds show the location of the dwellings of the Iangst people. Settlement banks used to be called shingle banks. They appear as round or oval recessed floor surfaces, surrounded by lacquer and sometimes metre-wide ramparts. The mounds usually contain large quantities of burnt stone and waste products such as bones and broken tools.

Spruce flats with wood fungi

The lesser crossbill feeds its young with spruce seeds and adjusts its nesting to when it is easiest to find cones with ripe seeds. The crossbill unties and splits the pine cone scales with its beak, so that the seed can be picked out with the help of a heavy ant. Spruce flame with wood fungi Spruce

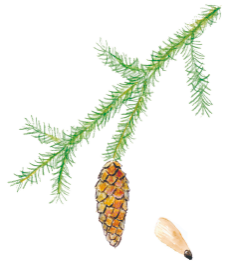

SPRUCE

Spruce is our most common tree and grows where there is a good supply of nutrients and water. Because of its shallow roots, it is easily blown over. It is then called 'flame' and becomes a vital habitat for many spruce forest organisms and thus for biodiversity. New flames are constantly needed, as each species can only live on the flame during a certain stage of decomposition. It can take up to 200 years for the wood to decay completely and for new spruce seedlings to grow on the remains of the nutrient-rich wood. The spruce flowers in early summer. The yellow pollen layer visible on water surfaces comes from male flowers. Once the female flower is fertilized, a cone develops, which matures in autumn and whose seeds fall out on sunny spring days when the cone bursts open.

Spruce cone and seed. The seed is attached to its own 'wing' which allows it to fly a long way before it lands.

SQUELCH MILL

In this place there was once a grist mill. It worked by damming the stream with stones, logs and earth. The water was released through a hatch into a water channel made of boards or stone. A water wheel was attached to a wooden shaft. This was the 'engine' of the mill. At the top of the wooden shaft were the mill wheels that ground the grain into flour. The grain was emptied into a funnel that sat above the mill wheels. Sometimes the stones were surrounded by a box that had an opening where the grain ran out.

Funnel Millstones Wood Shaft Water Heave

SUMMIT FOREST

The swampy forest has a high groundwater level. Some swamp forests grow poorly due to stagnant and oxygen-poor water. On the other hand, some soils can have high production due to moving and oxygen-rich water. Most of the swamp forests in our region have been drained in several rounds. Peaks in drainage activity occurred in 1914, 1933 and the last and highest in 1984. Nowadays, there has been more drainage and very little felling in swamp forests. Swamp forests provide good habitats for mosses and lichens. Frogs and beetles thrive here. If we want to find capercaillie, black grouse, grey jay and three-toed woodpecker, it may be appropriate to go to the swamp forest.

TAR PIT

The most common type of tar pit was funnel-shaped. The funnel was built up of small logs on a sloping base, on a hillside. On the inside, the funnel was lined with netting, which was laid in the same way as roofing shingles so that the tar could flow downwards. From the bottom of the funnel went the tar log, into which the tar would flow. The wood for the tar pit was cut from old pine stumps. It had to be short lengths (20-30 cm). The wood was packed standing along the sides of the valley. The logging continued until the valley had the shape of a round hill. The wood was then covered with a layer of spruce brushwood and wet moss. After this work, the tarred valley was lit. The first thing to flow out of the tar log was the tar sweat, a thin watery tar. This was to be utilised as it was thought to cure internal diseases. The tar sweat gradually became thicker and turned into pure tar. A valley with a diameter of 2-3 metres burned for about 16 hours and produced about 30 litres of tar.

ASPEN

There is only one species of aspen in Sweden, and in many ways it is one of Norrland's hardwood trees. In these regions, aspen can sometimes be up to 200 years old. No other tree species has so many insects, lichens, fungi and mosses associated with it, totalling at least 800 species. Our aspen is the most widespread deciduous tree species in the world.

In the past, the wood was used for roofing shingles, fencing, bowls, etc. Today, aspen wood is used for matches, furniture, toys and packaging. The bark and leaves of aspen can be used to dye yarn. The bark gives the yarn a black colour, while the leaves dye the yarn a bright yellow. In the past, the bark was used as a laxative and the leaves as a remedy for diarrhoea. Moose, sheep, goats and horses eat the leaves, twigs and bark of the tree with great appetite.

The aspen tick is a greyish-black, hoof-like tick that parasitises aspen. Birds' nest holes are often found right next to aspen ticks. The wood there is rotten and easier for hole builders such as certain woodpecker species to work with. In the past, the wood was used for roof

CATCH PIT SYSTEM

Moose and wild reindeer trapping pits are common ancient monuments in our woodlands and are therefore often affected by forestry operations. There are around 13,000 registered trapping pits in Jämtland County, but the actual number is probably much higher. The oldest dated trapping pits are from the Stone Age. Trapping was banned by law in 1864. Trapping pits can be isolated or sparsely scattered within an area. But they are often laid out in long rows, forming systems that can be several hundred metres or kilometres long. These systems have blocked off important game routes. When the pits were in use, there was some form of fencing made of cords or felled trees between the pits. The pits were covered with rice so that the animals would not detect them. Today we see the trapping pits as round or oval pits in the ground, 0.5 - 2 metres deep. The excavated soil lies like a mound around the edge of the pit. There are also pits that were intended for wolf trapping. Wolf pits are usually found on forest edges near settlements. The pits are usually round, 5-10 metres in diameter and surrounded by a low mound. When the pits were in use, the walls were lined with wood or cold-walled stone to prevent wolves from climbing out of the pit.